Jordan Series Drogue ... a Research

- Details

- Hauptkategorie: Jordan - Treibanker

- Kategorie: Jordan Series Drogue ... a Research

Jordan Series Drogue ... a Research

"I would never anchor a yacht stern-first against the sea in a storm!"

was my reaction when I first read about Jordan's Series Drogue on Dashew.

He would pull a yacht stern-first through a breaking sea?

Wouldn't a breaker sink the ship immediately!?

The impressive article "Heavy Weather Sailing?" (TO, July/09) by Ortwin and Elli Ahrens prompted me to investigate

the matter again. The results are worth sharing.

Name, Basic Design

Jordan, Donald (d. 2008)

...is the inventor of the JSD (Jordan Series Drogue®) and, as an aeronautical engineer, was involved

in the development of aircrafts that could take off and land from aircraft carriers.

He deliberately neither patented his "series drogue" nor commercialized the invention.

"drogue"

This word is used for anything towed when sailing out before a storm (lines, buckets, tires, modern sea anchors) to slow a ship

and keep it longitudinally aligned against the oncoming waves.1)

A whole series of braking systems has been developed overseas, one of which is the JSD.

"series" = series, row, sequence

It reflects the design of the Jordan drogue anchor:

Many canvas tubes (cones), sewn together like cones, open on both sides, are attached to a strong nylon cable

at intervals of about 1/2 m (with the larger opening facing the ship).

The number depends on the yacht's displacement.

Dacron cone sewn onto the towline

The cable has a weight at the end to keep the system submerged and under tension.

To better hold the boat against the oncoming waves and to halve the tensile forces on the boat's fastenings,

a "rein" consisting of two lines forming a "V" is sheared between the stern fastenings and the hawser.

Example of a Jordan drift anchor for a yacht with 8 t displacement:

- Length of towline: 76 m

- Number of Dacron cones: 107

- Length of rein: 2.5 x width of the stern (e.g., for a 2.00 m stern: 5.00 m)

- Weight at the end: 7 kg, e.g., chain

Rein / towline, equipped with Dacron cones / chain

Prices

There are several suppliers. For my yacht with an 8 t displacement (7 t + 1 t payload), a system with 116 cones

was recommended.

It would cost approximately € 700 to € 1.000, plus freight of approximately € 210 to € 290. (Jan. 2010)

Customs

- From EU countries, no customs duty and no VAT.

- From outside the EU: 8 % (for "ropes made of synthetic fibers") + 19% VAT;

(according to customs information, Tel.: +49 351 744834-510).

DIY

Earl Hinz and David Lynn 2) provide detailed information on how to build a JSD yourself.

Kits are available for purchase; they cost approximately € 600 to € 700 (2010).

Important figures are provided by the Coastguard Report, on which everything is ultimately based (see below).

Development

Donald Jordan, deeply affected by the Fastnet disaster of 1979, considers how yachts could survive such storms.

He noticed that after the disaster, although the construction of the yachts involved was examined, they did not examine

whether a sea anchor could have prevented them from capsizing.

This is where he comes in, using a scientific mindset and the tools of a modern engineer.

He starts his tests in his own test tank with boat models (long keel, moderate long keel, fin keel) and with a specially

constructed device to create breakers of varying mass and force.

From stroboscopically taken photographs, he calculates the acceleration and speed of the yachts when hit by a breaker.

How do they behave when hit broadside, or when lying in the direction of the wave?

Beyond a certain breaker size, which is in a certain ratio to the size of the yacht, all three models capsize,

regardless of construction or lateral plan.

Donald Jordan:

"The notion that a breaker 'hits' the boat and that the water from the breaker causes the damage is actually false.

In fact, the boat is lifted by the frontal rise of the wave, without impact.

When it reaches the breaking crest, the boat's speed is almost equal to the wave speed. ...

The damage occurs when the yacht is thrown forward by the wave and ... hits the trough."

(This and all subsequent translations are mine. Original texts, for example, at www.acesails.com.

See also "Breakers and Yachts" on this website.)

Now he is testing the use of sea anchors inopen water.

Jordan realizes that a sea anchor at the bow is not the right solution. Therefore, he turns to a stern-mounted solution.

Perhaps he was inspired by the way aircraft are slowed down when landing on aircraft carriers using arresting lines.

"When the yacht is hit by a breaking wave, its acceleration is so high, ...that the vessel takes no more than 3 to 3.5 seconds

to reach wave speed.

Therefore, a sea anchor must not only slow down, but it must also catch the boat before it is flipped or even capsizes over the bow. ...

This must happen within 1 or 2 seconds. ...

With a long, elastic rope and a brake consisting of only one element, this cannot be achieved."

Next, Jordan develops the sailcloth cones arranged one behind the other, an ingenious solution because the force

acting on each individual cone remains small.

The peak load generated by a yacht is related to its displacement.

Therefore, the number of cones must be adjusted to the displacement of the yacht.

This is followed by tests in a glass-walled wave tank to optimize the underwater performance of the new design.

Finally, realistic tests are conducted with a US Coast Guard lifeboat in the mouth of the Columbia River with its pronounced bar.

The Coast Guard Report (No. CG-D-20-87)

... – ultimately authored by Jordan – describes how the JSD works

and explains the tests; it contains tables on the forces involved, the number of cones required, and the strength of the tow ropes.

Jordan also explains how to manufacture the JSD there.3)

In addition to what has already been said, I will attempt to summarize the main points of the report:

- Most storms do not produce breaking waves. Sailors who have experienced such storms might be convinced

that the tactics used so far - heaving to, drifting, running away - are sufficient to prevent capsizing.

This is a grave mistake. It's not the height of the wave that's dangerous, it's the breaking sea.

None of the aforementioned tactics can prevent capsizing when a breaking sea strikes.

- When a wave breaks, a large volume of water cascades down the front of the wave.

This water moves at approximately the same speed as the wave itself.

- When the sail cones create resistance, the towline tightens and pulls the yacht over the crest of the wave

and through the breaker.

The forces acting on the vessel are roughly equivalent to the yacht's displacement.

- Highly elastic ropes are unsuitable.

The yacht could capsize before the braking effect takes hold.

(Note: Lines without stretch are also likely to be problematic; the peak forces would probably be too high.)

- Many sailors hesitate to deploy a sea anchor at the stern because they fear that the yacht will be damaged

if a breaker hits the transom, cockpit, and companionway.

Tests with the models show that this shouldn't be an insurmountable problem:

The stern has more buoyancy than the bow and rises with the wave.

Because the boat is accelerated to almost wave speed, the speed of the breaker is not much higher than that of the vessel.

- Nevertheless, a breaker can still enter, flood the cockpit, and hit the companionway.

When a yacht deploys a sea anchor, being in the cockpit is life-threatening.

- In the event of a serious impact, the acceleration, both linear and angular, can be very high.

- With a Jordan Drogue in tow, a solidly designed and built fiberglass yacht should withstand a storm similar

to the Fastnet Storm.

Note: This is, so to speak, the reference storm according to which Jordan designed its sea anchor.

Its test waves correspond to a real wave height of 7 – 10 m and an assumed wind speed of ~110 km/h (Beaufort scale 11),

as measured in the Fastnet Storm.

Some Figures From the Report

The forces that an incoming breaker would exert on the yacht are frightening.

According to Jordan ...

- the yacht's acceleration is approximately "2 g" (g = force of gravity) when struck by a breaking wave.

If someone were to be accelerated at 2 g for 1 second without safety equipment, they would be hurtling through

the cabin at ~70 km/h after that second,

and at ~140 km/h after 2 seconds. 4)

- The safety belts should withstand "4 g".

When accelerated by the wave, the ship is initially "straightened out" by the JSD, i.e., moved in a circular motion,

before it is decelerated.

It is almost impossible to predict in which direction one will be thrown inside.

Better than using lifebelts to tie yourself to something would probably be lap belts or three-point safety harnesses, similar to those in cars.

Even lying in your bunk, you'll have to be secured. If possible, in opposite directions (two lifebelts?).

I think:

- You should equip an ocean-going yacht with lifelines inside (near the bottom).

- You should also equip the vessel with a sufficient number of safety helmets.

Because: Crew members are unlikely to be convinced of the necessity of wearing a helmet beforehand.

As skipper, you also don't want to appear overly dramatic.

In this context, Dr. Jens Kohfahl's comments on injuries on yachts during heavy weather sailing are worth reading

(see "Storm Tactics for Yachts," on this website).

- … the stern, companionway bulkheads, and cockpit-side cabin walls should withstand a load

equivalent to a water jet pressure of 4.5 m/s.

Let's assume the companionway bulkhead is 1 m² in size. Then, under this force, the bulkhead

would be subjected to a pressure of 1 ton (1000 kg!),

and of course, its supports as well.

And the same applies to the stern and cockpit/cabin wall.5)

- On a yacht with an 8 - ton displacement, the cones generate a pull of approximately 6000 kp

(a 9 - ton yacht would achieve approximately 6700 kp).

More on this later.

Experiences

Dave Pelissier, who was the first to offer the JSD commercially (AceSails), states on his website:

"The Series Drogue has been at sea for over 20 years. Not a single boat has ever been lost …

Currently, I know of at least 50 cases, reported to me or published, in which the Jordan Drogue was deployed."

The Jordan Drogue occupies a special place among all current English-language authors who discuss storm tactics.

Also by Steve Dashew 6):

"There's no question: the Jordan Drogue works. A whole host of sailors have attested to this."

He continues:

“The problem is that the Series Drogue… perhaps works too well, so that - because the JSD holds the stern

to the oncoming sea - this and the parts in its immediate vicinity, namely the cockpit and companionway, are at risk.

Despite Don’s explanations, this remains a concern for us with boats that have vulnerable structures aft. …

On a yacht with a fixed stern and center cockpit, so that an oncoming sea doesn’t cause any problems, …

the Series Drogue is perhaps the ultimate weapon.

This also applies to flush-deck designs with a horizontal companionway hatch, where the sea cannot directly hit

the companionway bulkhead. …

In contrast, many cruising catamarans with their aft sliding doors are extremely vulnerable. …

The same applies to modern racing or cruising yachts with an open transom.”

The report by Robert Burns, which Dashew follows, is certainly intended as an illustration:

“My experience is based on a crossing of the Gulf Stream in June 1992.

I encountered conditions generated by sustained Force 10 winds for about 18 hours. … The wave height averaged 9 meters.

I was captain of a center-cockpit yacht, a Contest 40 (8 tons) …

We ran for about 6 hours, surfing down the breaking seas. Continuing in this manner was too dangerous,

and at nightfall, we launched the Jordan Series drogue stern-to. …

At the height of the storm, we lost the Jordan Drogue. The towline had chafed through. …

Within moments … we were broadside to the sea.

We were struck by a breaker …

The incoming wave smashed the companionway bulkhead and flooded the saloon. …”

Water in aft cabin and engine room, companionway smashed, saloon flooded - this on a center-cockpit yacht, where, according to Dashew, "a boarding sea doesn't cause any problems."

The lesson:

Anyone equipping themselves with a JSD must massively reinforce all vulnerable areas if their structure isn't beyond reproach,

and above all: chafing of the towline must be eliminated.

Because the accident wasn't actually caused by the Jordan Drogue, but by the fact that the towline had been incorrectly attached.

It's noteworthy that Dashew seems to have abandoned his initial critical stance towards the JSD.

On www.setsail.com/heavy-weather-issues he says:

"We can foresee two types of drogues being used. In severe but not survival conditions we may want to deploy

a simple drogue like the Gale Rider. This will hold the stern more or less into the seas, and allow us to move forward at anywhere from four to eight knots, with control of our direction still under the command of the auto pilot or one of us.

The second situation could occur in survival weather – absolute horrendous conditions – with he boat disabled, in which case our choice would be the Jordan Series Drogue.”

(Text as I perceived it in 2013)

Addendum, February 2026

Susanne Huber-Curphey

Susanne Huber-Curphey

*(from: "Our Experiences with the Jordan Series Drogue (JSD)" in: Trans-Ocean, Jan. 2011)*

"I read with interest the article ... by Dr. Lampalzer on the Jordan Series Drogue (JSD).

Unfortunately, the text tends to evoke fear of the forces generated when the drogue brings the boat to a halt,

rather than emphasizing that, in our opinion, the JSD is the ONLY SAFE method for surviving an extreme storm aboard a yacht.

Unfortunately, the text tends to evoke fear of the forces generated when the drogue brings the boat to a halt,

rather than emphasizing that, in our opinion, the JSD is the ONLY SAFE method for surviving an extreme storm aboard a yacht.

My husband Tony and I have deployed the JSD a total of 11 times over the past eight years ... and in every instance

we survived the heavy weather – including some terrifying breaking seas – well and without any damage!

Once the JSD is deployed, the yacht lies surprisingly stable with its stern to the sea. When a breaker comes charging in

(which can happen every five minutes), the boat is first aligned precisely with the direction of the waves

(this works well even in cross seas), thus preventing a broach and a massive, lateral impact.

Then the lines take the strain – but without any hard jerking, because the individual cones of the JSD never absorb

the boat's acceleration all at once. It feels exactly as if a giant rubber band is bringing the boat to a halt quickly yet gently, safely and without danger.

Under certain circumstances, a breaker may come in over the stern, but in almost all cases it roars past sideways

along the hull – and I never had water on the foredeck or the coachroof. ...

The dramatic boat movements described inside the cabin are in fact harmless.

As long as the drogue does not chafe through and there is no risk of collision with another vessel

As long as the drogue does not chafe through and there is no risk of collision with another vessel

(AIS is very helpful!), you can actually relax below deck.

However, the boat will make strong, but never dangerous, rolling movements."

However, the boat will make strong, but never dangerous, rolling movements."

Addendum, Oct. 2025

Susanne Huber-Curphey

(from: One and a Half Times Nonstop Around the World… in: Trans-Ocean, Oct. 2025)

TO:

The leg from Tasmania to New Zealand was quite something. Not only was the weather very severe, but a cyclone

with winds exceeding 80 knots was also waiting off New Zealand. What helps you weather such severe storms?

I'm not prone to panic, but every storm is a physical and emotional challenge.

What reassures me is knowing that I have a truly reliable storm tactic with the "Jordan Series Drogue" (JSD). ...

The secret of the JSD lies in the fact that the load from heavy breakers is distributed across these many small funnels. Thus, there is no sudden shock load.

In fact, it feels as if the boat is hanging from a gigantic rubber band in total safety. ...

The Jordan Sereis Drogue was in the water seven times this time. When do you decide to deploy it?

How do you secure it? And how do you get it back on board?

... Depending on the conditions, I hoist the trysail at around force 8, the storm jib at 9, and up to force 10, I can still walk safely under the tiny storm jib for a short time.

Anything above that brings dangerously high breaking waves in which Nehaj, despite her very high stability,

would be thrown sideways onto the water or roll over.

Then it's time to launch the JSD. ...

After that, there's nothing more to do outside, because all the sails are furled, the tiller is fixed in the middle,

and the rudder blade of the windvane autopilot is removed.

So, hatches closed and weather the storm safely inside.

Regarding the deployment:

(I) strongly recommend starting with the line at the stern and using it to slowly and absolutely under control

lower the entire JSD, so to speak, in a large loop.

Finally, the end weight is released and sinks vertically.

(Addendum:

I have enclosed the terminal weight (approx. 8 metres of 10 mm anchor chain) in a bag

which I deploy entirely, because an open length of chain could thrash around like a whip ..."

from: "Our Experiences with the Series Drogue", ibid.)

I have enclosed the terminal weight (approx. 8 metres of 10 mm anchor chain) in a bag

which I deploy entirely, because an open length of chain could thrash around like a whip ..."

from: "Our Experiences with the Series Drogue", ibid.)

The most commonly recommended method, simply letting the JSD run freely, poses significant risks.

The numerous small funnels can become entangled on a winch, a cleat, or even within themselves under high load.

Complete autopilot systems have been torn off in this way ...

Addendum, Feb. 2026

Drift speed

In extreme conditions, with a correctly sized and deployed JSD, you can expect

a controlled drift speed of approximately 2 knots (± 0.5 knots).

This speed is sufficient to maintain control and prevent pitchpoling, yet slow enough to manage

the stresses on the vessel effectively.

The exact speed will depend on the factors mentioned above.

(Note: namely strenght of wind, heights of waves.)

Metal Boats

Owners of metal boats have it relatively easy.

They probably don't need to worry about the stability of the stern and cockpit/cabin bulkhead.

They will likely want to replace the companionway boards, ideally with carbon fiber plates.

However, this isn't cheap.7)

It would be half as expensive to glue thin carbon fiber sheets onto the boards.

For an 8 mm board (marine plywood), a 2 mm (or better yet, 3 mm) thick bidirectional carbon fiber sheet (CFRP)

should be sufficient to avoid breaking under the assumed water pressure.

The The carbon fiber plate would have to be glued flush and immovably to the plywood on the inside (!)

of the companionway.8)

However, there will still be some deflection, in the worst case so much that the board jumps out of the U-shaped guide.

My friend, Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Ulrich Schleicher, would build a kind of "shield" that overlaps the companionway laterally,

made of 18mm plywood with two layers of 500g/m² roving on both sides.

It must be securely fixed, as it will also be accelerated somewhere at 2 g.

Eyelets would have to be welded to the stern, to which the JSD would be shackled.

Eyelet thickness and shackle pin diameter at least 15 mm (steel) for a yacht with an 8-ton displacement.

(See below).

GRP and Wooden Yachts

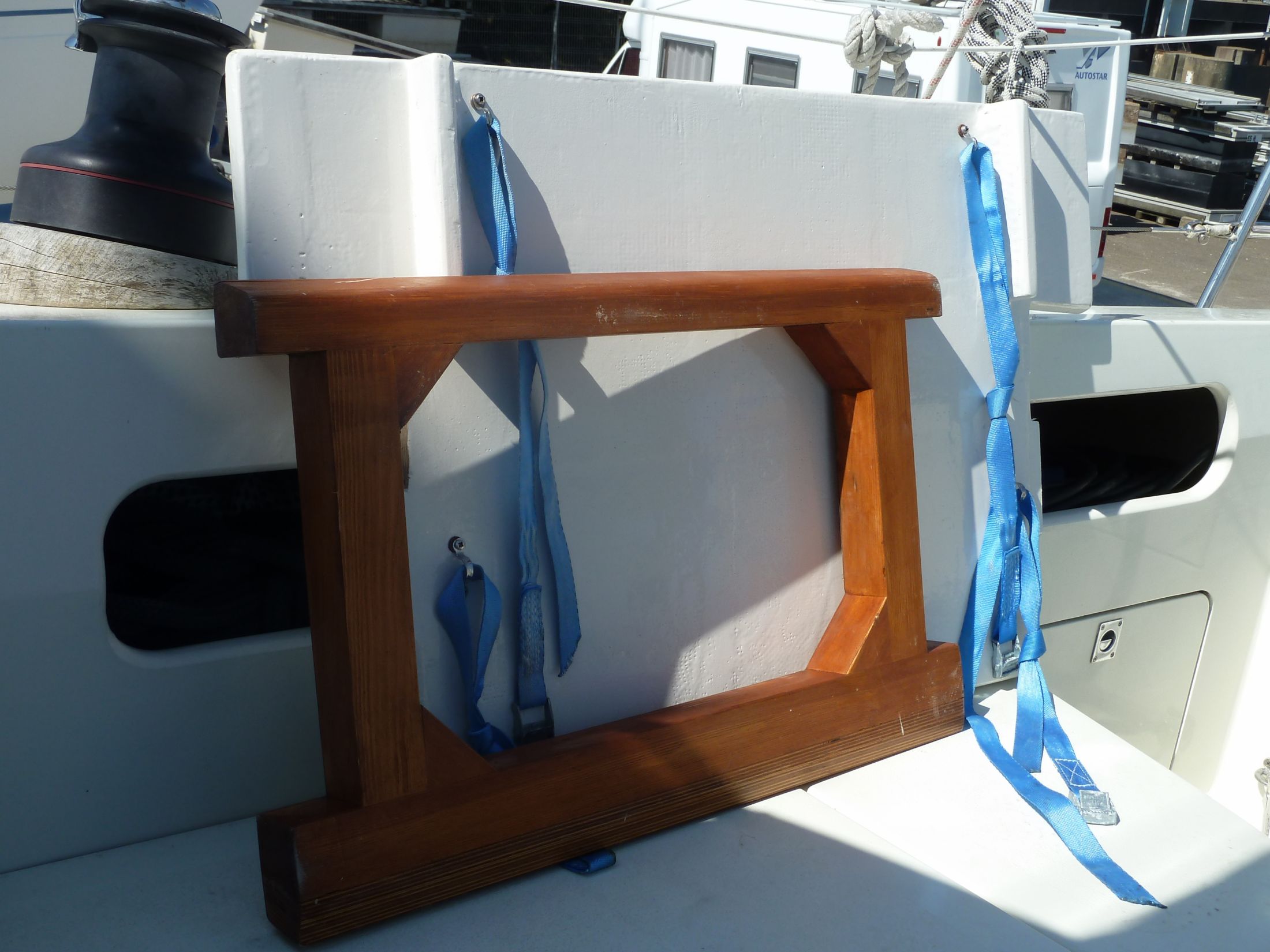

Anchor points for the JSD

Jordan advises against cleats or winches over which the JSD is placed; they could be pulled out of the deck.

He recommends chainplate-like, horizontal anchor points.

These should be bolted to the top of the hull sides, directly forward of the transom, so that their ends protrude slightly aft.

The stainless steel plates should have holes drilled there, into which the JSD is attached with shackles.

David Lynn lists dimensions of these stainless steel plates for different vessel sizes; he has also scanned photos.9)

On an 8-ton yacht, the cones generate a pull of approximately 6000 kp (a 9-ton yacht would achieve approximately 6700 kp).

This force is roughly halved, since it is absorbed by two attachment points.

Jordan calculates 70% of the load at each point because the pull is only very rarely in direct line with the ship.

This would result in a force of 4200 kp (and 4700 kp at 9 t displacement).

This in turn necessitates a long stainless steel plate measuring 700 x 70 x 10 mm.

According to Lynn, it must be fastened with 10 bolts (10 mm diameter). I consider this excessive.

If a single 20 mm diameter shackle bolt (stainless steel) is sufficient (next section), four 10 mm bolts should also be adequate.

Every additional hole unnecessarily weakens the hull.

The distance between the aft edge of the hole, which is intended to hold the shackle for the JSD, and the end

of the stainless steel plate should be at least 12 mm to prevent the steel from tearing out;

15 mm would be better, and 20 mm for stainless steel. 10)

This also means that the shackle and the diameter of the shackle pin, with which the JSD is attached,

should be dimensioned similarly: 15 mm for steel, 20 mm for stainless steel.

Attaching a rein to the stainless steel plate

Hull reinforcement

David Lynn mentions that on a fiberglass boat, the hull would need to be reinforced at the attachment points

with additional layers of fiberglass. In my friend's opinion, this is far too little.

For my boat, a woodchore epoxy yacht (i.e., a yacht with a wooden core), he recommends:

- First, install an 18 mm plywood sheet on the inside, significantly larger than the stainless steel strip on the outside.

The plywood sheet should be joined as flush as possible with the hull using epoxy filler.

- Secondly, and most importantly, install a solid 6 mm thick stainless steel backing plate on the inside,

with the same dimensions as the outer stainless steel plate.

.JPG)

Plywood with backing plate on the inside

The hulls of GRP yachts, whose core consists of foam, are prone to be dented in when forces are applied at a single point.

Therefore, I first would reinforce the area with marine plywood over a large area where the stainless steel strip

is to be attached to the outside.

For this, the inner shell must be cut open and the foam removed. A solid bond can be achieved with epoxy filler.

Next, laminate the reinforced area with overlapping fiberglass fabric. Only now you can attach the aforementioned

18 mm plywood plate plus stainless steel strips.

It would be advisable to seek the advice of a professional.

Furthermore, my friend believes it's important to check whether the ship's stern spars are sufficiently strong.

In my example (4200 kp pull), a lateral load of approximately 1450 kp is generated (at a pull angle of 20°).

A square steel tube, precisely fitted as a support between the stainless steel mounting plates, as close as possible

to the attachment point for the JSD, significantly improves the design.11)

Square tube between the mounting plates

Do not confuse this with the (round) support tubes of the Aries autopilot system.

Reinforcing the stern with rovings seems relatively easy.

However, I can't say how many layers will be necessary at a water pressure of 1000 kg/m².

It might be necessary to install additional longitudinal support walls, which would themselves require bracing.

View from above into one of the lazarettes: Longitudinal support wall

The dilemma begins here:

The hulls of modern ships are self-supporting; the classic longitudinal stiffeners to which the supports would have to be attached

are missing.

A real problem!

This applies equally to the…

Cockpit/cabin bulkhead

It should be reinforced.

On my boat, I did this with 18mm plywood and two layers of 500 g/m² roving.

However, it remains to be seen whether the bracing of the entire cockpit/cabin bulkhead will hold.

Reinforcement of the cockpit/cabin bulkhead; it was subsequently filled with filler.

Companionway

A reinforced companionway bulkhead would bend under water pressure.

This creates a force that pushes the walls outwards.

This process can be roughly compared to the effect of a wedge.

One doesn't feel comfortable with this solution, at least not with GRP or wooden structures.

Therefore, the aforementioned shield also is useful here.

On my boat, I've divided it horizontally into two parts.

The lower part is permanently installed at the beginning of a serious voyage, the upper part only when needed.

The lower part of the shield and its support (abutment).

Of course, the partially installed shield is somewhat cumbersome underway. But one gets used to it very quickly.

The advantage is that a space is created between the companionway bulkhead and the shield, which can temporarily

accommodate halyards and lines, for example, when reefing.

It also provides a protected, secure footing when working on the deck winches.

The upper part of the shield is deployed in an emergency and secured in a similar manner.

The JSD is ready for use.

The weight (chain) is located in the aft lock.

In an emergency, it would be released overboard aft. This would cause the entire JSD to pull in and deploy.

(I would change this arrangement on Susanne Huber-Curphey`s recommendations today.)

Inside the yacht

… the crew must be able to secure themselves: hook eyes, lines, 3-point safety harnesses …

Retrieving the JSD

There have apparently been several instances of considerable difficulty in retrieving the JSD.

One has to wait until the storm subsides, and even then, in some cases, it took several hours, despite the use of winches.

An additional retrieval line, shackled to the V-point of the rein, is recommended.

It also seems practical to subsequently attach a line with a stopper knot to the JSD's hawser and pull it in.

If working with two lines, one can alternate retrieving.

Evans Starzinger

"...the load on the Don Jordan`s Series Drogue rode is not at all static or steady.

It's in fact very highly cyclic, being highly loaded when the bow is pointing down the face of a wave and lightly loaded

when the bow is pointing up the back of a wave.

This has two implications for retrieval:

It’s actually quite possible to ‘manually’ retrieve the rode by spinning the winch quickly for 3 or 4 turns

during the low load portion of the cycle and resting during the high load portion of the cycle. ..."

Conclusion: If the bow is pointing up, reel in. Because then the pull is small.

Susanne Huber-Curphey

Contrary to many false opinions, retrieving the JSD is not a problem. ...

Two factors are crucial here:

First, the JSD has just safely and undamaged brought you and your boat through a severe storm.

In comparison, it's unimportant if hauling in takes about two hours;

some report needing only one hour.

Second, there's always a high sea after the storm, which is very helpful when hauling in.

Because when the boat is in the trough of the wave, the tension on the line is briefly very low or even completely slack.

I wrap the thick JSD line twice around my large cockpit winch, and then haul in the line when there's no tension on it.

I never use a winch handle.

- - - - -

Long Keel Yachts?

Jordan experimented with stationary yacht models.

A stationary vessel cannot create a vortex zone; for that, it must be drifting dynamically.

Helmut von Straelen's experience report "Heaving to in a hurricane?" (Beidrehen im Orkan? TO/Oct 2007 and on this website)

shows

that the large long-keeled boat can heave even in extreme conditions.

But what are the limits for small long-keeled boats? What about boats with a "cut-off forefoot"?

Bernard Moitessier

"In the high southern latitudes, an easterly storm will not produce unusually high waves, even if it blows very hard.

In such a situation, I think it is quite possible to remain hove-to without the danger of being rolled by a large breaker.

These breakers would only reach moderate height, and the vessel could take advantage of the protection of its own windward vortices,

whether it is a 12-meter vessel or a much smaller one. ... The lateral water vortices of the drifting vessel

smooth the breaking crests, just as a layer of oil would.

Our situation is, of course, quite different if the storm blows from the west, from the same direction as the large swell

that is always present in the high southern latitudes.

Under the pressure of a powerful storm, this swell can quickly become enormous and build up gigantic breakers, against which

the windward vortex of a hove-to vessel has no effect at all, at least not that of a heavy 12-meter vessel.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the wave crests generated by westerly storms are generally less high…

Therefore, it is rare for yachts hove-to to be badly damaged, but rare does not mean never … I

n the book "Heavy Weather Sailing" (note: by Adlard Coles), there are photos of breaking wave crests

that absolutely no hove-to yacht could have ridden.

These photos have been taken in the Atlantic, between 30° and 35° north."

(from: Moitessier, "Open Seas, Islands and Lagoons")

The question arises whether the JSD is still effective under these conditions?

Donald Jordan seems confident.

(See Donald Jordan, Selected Texts: "The Loss of the WINSTON CHURCHILL". On this website.)

Summary

The authors agree that ships must never be struck broadside by breaking waves.

Hinz mentions two values (12):

- If the wave height is approximately equal to the ship's beam, the breakers can capsize the yacht.

(In his opinion, tacking against them then is too dangerous.)

- If the wave height is approximately equal to the ship's length, even an upside-down capsize is possible.

Because steering errors become more likely when running as fatigue increases, in his opinion, modern sea anchors

are a sensible option.

Steve Dashew (“Surviving the Storm”) recommended the following for short-keeled yachts:

- to heave to initially to conserve energy,

- but steer manually from the moment of the passage of the low

- initially, perhaps, head upwind,

- if this is no longer possible, running.

However, Steve Dashew now recommends both the Galerider and the Jordan Series Drogue.

(More details in “Storm Tactics for Sailing Yachts”.)

But what to do when strength is waning?

Then you'll be grateful if the boat is held in front of the waves by a brake.

The Jordan Series Drogue obviously performs this function flawlessly and without putting the yacht under extreme stress.

That's a significant advantage.

Jordan actually designed its sea anchor with the aim of bringing a vessel through a storm, even in Fastnet conditions.

The positive testimonials published by the manufacturers should only be trusted to a limited extent.

Simply buying a JSD is not enough, nor is implementing the rather amateurish suggestions from the internet

for improving your own fiberglass yacht. This leads to a false sense of security.

The meager figures provided by Jordan only offer a vague picture of what happens to a vessel caught in a breaking sea.

Nevertheless, a yacht, even one that hasn't been upgraded, fares better with the Jordan Series Drogue than without.

However, if the yacht is appropriately reinforced or was designed for it from the outset, it likely has a real chance with the JSD,

even under extreme conditions.

Ed Arnold:

"I used the JSD several times, for safety reasons and to hold position. …

I have deployed it three or four times due to breaking waves.

The first time was in the North Atlantic south of Iceland in Force 10 winds and waves of 8 meters or more.

The boat was held at a 30-degree angle with the stern to the wind. …

The cockpit got very wet; at times almost dangerously. Incoming waves repeatedly filled it, but none broke directly over us. …

I had similar results in the Gulf of Alaska and near Cape Horn. …

I always felt safe, although a wave breaking fully on board could really cause damage. …

The stern and companionway of my long-keeled aluminum yacht are designed to handle a breaking wave.

Some yachts wouldn't be strong enough for that." 13)

I am convinced that the Jordan Series Drogue will prevail.

GRP vessels designed for the high seas will be available as an option for JSD -compliant construction in the future.

Hal Roth:

“This specialized drogue designed for the ultimate storm is not cheap, the hull connections are complicated,

and you may never use it.

But who can tell when another Fastnet disaster will occur?”

- - - - -

Frontal Passage (Addendum Aug. 2016)

Dashew:

"One of our concerns is about what happens in a frontal passage when the wind and sea shift 90 degrees:

The drogue line is so long that it tends to take an average position to the wind and wave trains.

The vessel, however, will align itself with the current wave it encounters.

In other words, the vessel will align itself stern-to the wave that is passing under the hull.”

What danger do the breakers stem from the “old” wind direction?

None!,

replies Jordan.

"There are no breakers without wind propulsion."

Breakers only occur after a wind shift, originating from the new wind direction.

What remains are the very steep and high walls of water that result from the superposition of two wave systems.

"A large storm wave approaching the boat appears to be a dangerous wall of water…

Actually, the water in the wave is not moving towards the boat and will lift the boat harmlessly."

… when it is in front of a JSD.

“From physical considerations it is virtually impossible for a breaking storm wave to approach from a significantly different direction.

Breaking waves are formed by the wind and by the addition of the energy of the smaller waves that they overtake.

If a wave moved across a series of smaller waves it would lose all its energy in turbulence.

We have many aerial views of the sea surface in the Sydney-Hobart storm.

If a large wave had moved across the smaller waves we would see a white streak, running across all the other streaks.

There is no such a streak.

What actually happens is that if the boat is lying at some angle to the prevailing sea as the breaking wave

approaches, the action of this wave yaws the boat until it is abeam.

This yawing motion is not observed by the skipper and he thinks the wave direction has changed,

whereas it is the boat that has moved."

Despite his initial skepticism, Dashew now (2014) equips his motor yachts with the Jordan Series Drogue.

Dashew is one of the most renowned designers in America today. He has written the most important book

on storm tactics ever written.

When he recommends something, it's like being knighted.

— —

Addendum (Dec. 2016)

Ortwin Ahrens, now in Whangarei, in northern New Zealand, is the base manager for Trans-Ocean.

He recalls:

"Many years ago, we saw a film in the USA by the Coast Guard about tank tests with the Jordan Drogue,

in which three different yacht types were tested with and without the Drogue in increasingly higher waves.

Without the Drogue, all of them eventually capsized; with the Drogue, none did. That was quite convincing.

We've been sailing for 50 years and are probably among the first to have used the Jordan Drogue.

We think it's the best thing there is."

(Martin Muth, "Wie Jordan auf die Trichter kam ..." in: Nautical News 4/2016)

- - - - -

Addendum (Sept. 2017)

The JSD has long since become standard equipment for many offshore sailors.

Trevor Robertson, for example, used it six times on his voyage from Newfoundland around the Cape of Good Hope to Australia,

sometimes under extreme conditions.

A few sentences from his report:

"… the wind quickly built to north-northwest violent storm force 11 (60 - 64 knots).

I let the drogue out again and IRON BARK ran steadily on with no sign of broaching.

The drogue sometimes held the stern down enough for the top of a wave to fill the cockpit but we were never heavily pooped.

The seas were huge, majestic and terrifying ...

In summary, I think the series drogue is a valuable, perhaps lifesaving, aid to small vessels in heavy weather.

It is worth its considerable cost and the nuisance of its weight and bulk, despite the problem of the cones

having a relatively short life."

www.morganscloud.com/2017/05/19/battle-testing-a-jordan-designed-series-drogue/

The cloth quality of the cones should be improved.

Further JSD deployments can be found at www.jordanseriesdrogue.com./D_2.htm ("Performance at Sea").

- - - - -

Addendum (April 2018)

From the series "Heavy Weather" by Heide and Erich Wilts:

"The Jordan Drogue, in particular, has impressively demonstrated its suitability both in the towing tank and in practical applications.

We consider it just as important as a life raft and an EPIRB."

- - - - -

Addendum (June 2021)

There are now several informative videos available, e.g.,

- - - - -

Footnotes

1) The German term "Treibanker" was previously defined by a specific form and had negative connotations.

Originally, I had chosen "tow brake" or "tow anchor" as translations for "series drogue."

However, "Treibanker" seems to have persisted in sailing terminology.

From now on (July 2018), I will use the term "Jordan Treibanker" to distinguish it from the earlier sea anchors.

In the English version: always Jordan Series Drogue

2) David Lynn, "Heavy Weather Sailing – Making a Series Drogue," www.nineofcups.com.

Here you can also find dimensions for the stainless steel mounting plates for different displacements.

3) The report can be downloaded from the internet, including from Wikipedia,

keyword: "Jordan Series Drogue."

Conversion from English Units:

1 inch (in) = 2.54 cm / 1 foot (ft) = 30 m / 1 pound (lb) = 0.45 kg

4) 1 g corresponds to ~ 9.81 m/s², so 2 g corresponds to ~ 19.62 m/s².

If this force acts for 1 second, the result is:

Speed = Acceleration * Time = 19.62 m/s² * 1 sec = 19.62 m/s = 70.632 km/h.

5) If a current traveling at speed v encounters an obstacle and is completely decelerated,

a density ρ of 1025 kg/m³ is created in the seawater.

p = 0.5 * 1025 kg/m³ * 4.5² m²/s² = ~ 10378 ((kg * m²) : (m³*s²)

= kg : (m*s²) = (kg * m) : (m²*s²) = 10378 N/m².

1 N corresponds to the weight of 100 g, so 10378 N corresponds to the weight of 1037.8 kg.

(according to Dr. W. Sichermann)

Jordan doesn't mention whether he factored in a safety surcharge.

6) Dashew, "Surviving the Storm", p. 435 ff.

7) Approximately 1 m² of carbon-epoxy sheet (CFRP), 5 mm thick, currently (2010) costs about € 650;

approximately 1 m² of carbon sheet, 1 mm thick, costs about € 325; approximately 1 m² of carbon hybrid

(carbon core layers, E-glass face layers), 1 mm thick, costs about € 295.

Available, for example, from Carbon-Composite.

Carbon sheets can be processed fairly normally: sawing, drilling, and bonding.

Their cut edges must be sealed.

See, for example, www.carbon-blog.de for information.

8) The calculations for this (and all subsequent ones) were carried out by my friend, Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Ulrich Schleicher.

The following parameters were assumed:

- The pressure does not occur suddenly; Area: 1 m²; Plywood: 8 mm;

Zero line of the compression-tension curve: at the boundary between the two materials

- Tensile strength of the bidirectional fabric: 1300 N/mm² (according to www.carbon-blog.de)

- Safety margin: 100%

The carbon composite bulkhead would roughly achieve 830 N/mm².

However, not all carbon is created equal.

The tensile strength should be confirmed by the manufacturer.

This and all other design suggestions come from Dr. Ulrich Schleicher.

9) David Lynn, www.morganscloud.com, keyword “Heavy Weather”. Unfortunately, the values are not verifiable.

10) Calculation with the following values:

Elongation at break of steel 500 N/mm²; tensile strength 4000 kp, safety margin 50%.

The tensile strength of stainless steel is slightly lower, approximately 20 mm.

11) Lateral force = 4200 kp * sin 20° (tension angle) = 1436 kp; at 30° it would be 2100 kp.

The square tube prevents the side mounting plates (on the outside of the hull) from bending inwards.

Furthermore, the tensile forces are always distributed across both plates.

12) E. Hinz, Heavy Weather Tactics, p. 14

13) Quoted from Hal Roth, p. 130

- - - - -

Literature

Bruce, Peter, "Adlard Coles - Heavy Weather Sailing", 62008 Dashew, Steve & Linda,

"Surviving the Storm", 1999

Hinz, Earl, "Heavy Weather Tactics – Using Sea Anchors & Drogues", 22003

Roth, Hal, "Handling Storms at Sea", 2009

Websites

- - - - -

Research and calculatio were carried out to the best of my knowledge and ability. I assume no liability.

The accompanying images were taken on our yacht "Summertime".

Dr. Lampalzer, Feb. 2026

Original text in German

translated by Google Translator in Nov. 2025